There is awareness that Australian cities and towns face significant future headwinds from environmental and climate change. This is important because, as market research company Ipsos notes, access to natural environment is a strong factor driving liveability in both metropolitan and regional Australia.

Many cities and towns are turning to emerging technologies for environmental monitoring to ensure that quality of life for all inhabitants can be maintained.

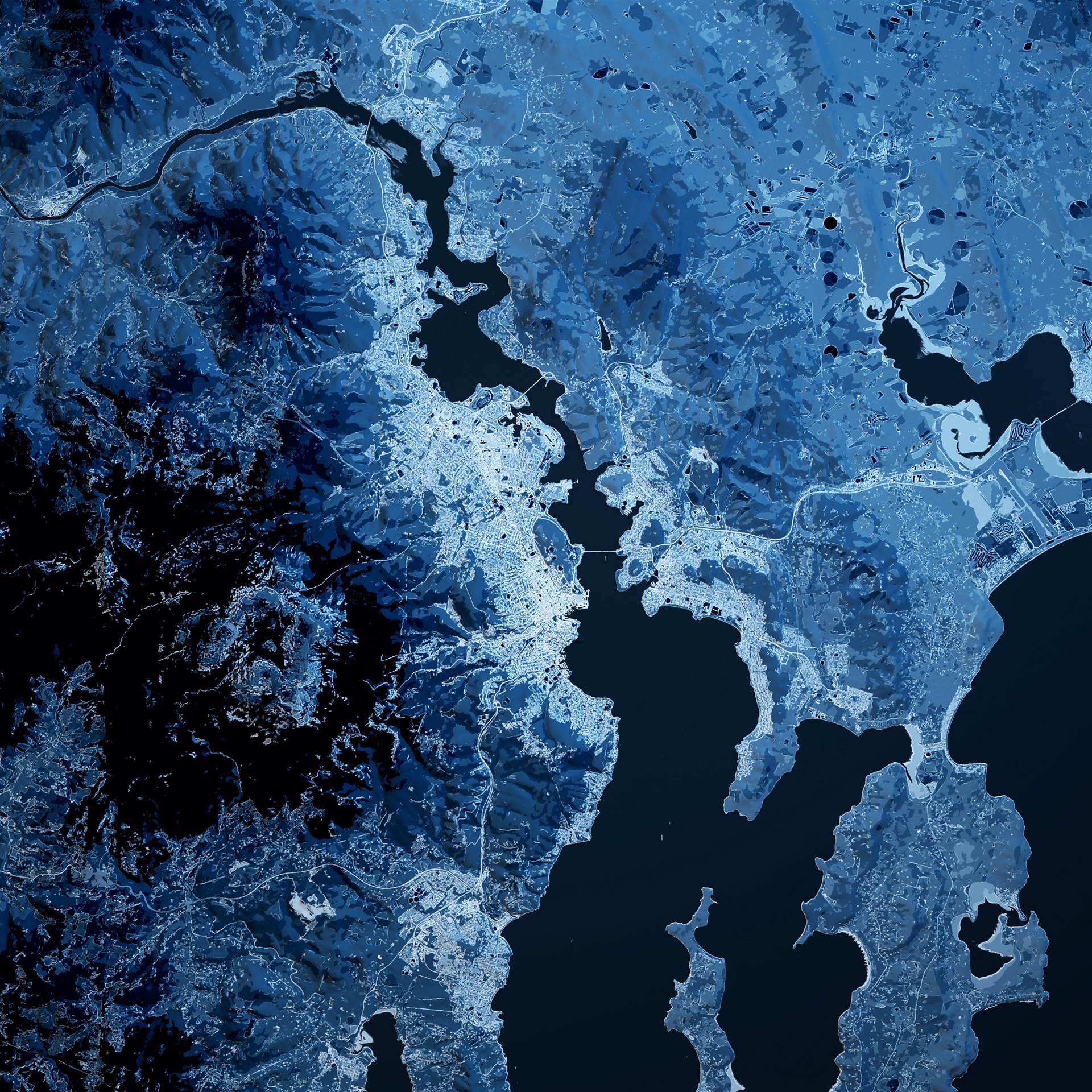

Environmental inclusivity and sustainability is critically important to the City of Hobart.

It is taking a broad view of environmental monitoring, with specific initiatives targeting “emissions, heat, noise, wind, fire, snow, smoke and light”.

At the time of writing, the city had run experiments with several environmental monitoring stations and sensors, and was preparing a request for quotation (RFQ) for its chosen solution.

“We've done a site survey of the city, we know where the monitoring stations are going, we know what the middleware, data bus and [presentation] dashboard is going to look like,” director of city innovation Peter Carr says.

“Now we've just got to put the final sensors out there.”

One thing that sets the City of Hobart’s environmental monitoring program apart from others is that it is not market-driven: that is, council is not content to “just put some CO2 monitors out and see what happens.”

Environmental monitoring is one facet of the City of Hobart’s ‘Connected Hobart’ action plan, which aims to address challenges that the city faces both now and into the future through 62 projects in the next five years.

Carr says the city was surprised at just how much it could potentially achieve with environmental monitoring. “We were really surprised when we started to scratch the surface.”

Granular data

.

The most obvious application, according to Carr, is getting access to more granular data about the city’s emissions, which will provide a closer to real-time view of environmental emissions.

“Capital cities and other major regional cities have been publishing community emission profiles for a number of years,” explains Carr.

“In terms of getting on top of our emissions, we've got three big areas one: cars is obviously a key one, our waste centre is another, and we have cruise ships numbered “in the low 70s” that visit each year.”

The city is also working with the University of Tasmania to research the city’s profile and identify ‘heat islands’ - urban zones that experience high temperatures due to surrounding human influences.

“The rollout of environmental sensors across the city is going to give us a much more granular view of what our heat islands look like,” says Carr.

We have some specific urban cooling projects that we'll be doing off the back of that. At a very practical level, we even have an annual allocation for the rollout of street trees and so having that additional heat environmental data at a layer below what we could get from the Bureau of Meteorology, for example, is fantastic for that.

“It also allows us to work with the community to give them a better idea about what a climate-ready home looks like and the heat and environmental influences around that.”

Sensors could also help the city manage other environmental influences.

When Hobart gets too windy, Salamanca Market - a major tourist draw - needs to be closed. “That's not an insignificant thing, so having more granular detail around that and being able to communicate it in real-time to the community through our city dashboard that we're building [will be helpful],” Carr says.

The city’s geography means it is surrounded by bushland, raising the risks from fire. “Fire and smoke detection using environmental monitoring stations is important for early detection. It also will allow us to have a forward view, not just for emergency services but some strong community indicators for things like respiratory issues and then taking it to the next level, trying to get ahead of things like asset losses and events like that.

“At the complete opposite end of the spectrum, it snows down here, and when it does snow quite heavily, we often have to shut roads, close walking trails and tracks and things like that because we're trying to preserve life and and it gets pretty dangerous in those conditions. So having environmental monitoring for those temperature extremes is important.”

One other environmental aspect that the city is sensitive to is light pollution. It has scoped a draft initiative, for consideration by the community, called ‘Reclaiming the Dark Skies’ under a program called Sustainable Hobart, which is a sister program to Connected Hobart.

Light pollution is one of the most significant environmental pollutants today and we're really keen to see how we can use our monitoring to try to slow down if not stop if not reverse some of our night-time lighting pollution.

“If you get your lighting right, it can be a driver of economic development because people want to be outside at night, but it also has a direct environmental impact as well because a lot of the wildlife in and around the city is nocturnal and impacted by the city’s lights.”

Keeping Adelaide and Ballarat cool

.

The City of Hobart is not alone in its use of environmental monitoring to improve the liveability of urban areas.

SA Water is currently trialling more than 200 air temperature sensors in public spaces and playgrounds across metropolitan Adelaide. The trial involves technology partners SWAN Systems and uses connectivity from Fleet Space Technologies and The Things Network (TTN).

The purpose of the sensor network is to show citizens the coolest areas of the city in real-time. Since the trial began in late February, SA Water says it has found an average three to five degree difference between “green irrigated sites and non-irrigated spaces in the same suburb.”

SA Water’s manager of environmental opportunities Greg Ingleton says the initiative builds on an earlier heat mitigation trial at Adelaide Airport.

"Cooling occurs due to the evaporation of moisture from the soil and the transpiration of moist air from vegetation, and is something that can be easily maintained with a relatively small amount of water,” Ingleton says.

“By applying smart irrigation principles we have developed with service provider SWAN Systems to maintain healthy lawns and vegetation at parks and playgrounds, we can easily show the positive impact on creating cool public spaces people can enjoy in hot temperatures.”

Telling people where they can find cool green spaces could encourage them to stay outdoors rather than inside under an air-conditioner.

Ingleton says such projects could help councils “make cost-effective decisions about their irrigation practices” and to reduce the creation of urban heat islands.

SA Water says it is providing data to councils “to compare irrigation patterns to any temperature reductions achieved, and help make informed decisions on future park upgrades or investments.”

The utility hopes to add more parks and reserves in regional areas of the state in the future. It also hopes to see individual households apply some of the lessons learned.

The ultimate outcome is that we, as a state, maintain and possibly increase the amount of green open space which includes both public and private space (i.e people understanding the concept and doing the same in their backyard).

The success of the trial will be judged “on a few aspects including the number of hits on the website, the number of councils that promote it through their websites, and feedback from our networks,” he adds.

Another environmental monitoring project underway with a liveability focus is the Digital Living Lab at the artificial Lake Wendouree in Ballarat.

The City of Ballarat has recently installed sensors around the lake “to measure a range of atmospheric and water-related data including the current temperature, wind speed and wind direction.”

It’s also using pedestrian counters to measure how areas around the lake are used as well as smart bins to manage waste.

Data is being transmitted from the sensors via TTN and then published online in an open data platform.

Managing water

.

City of Ballarat’s Lake Wendouree supervisor Bernard Blood says the lake’s climate can vary considerably from Ballarat Airport, where official weather data is recorded.

Lake users benefit from the information. “For instance, access to wind direction and speed allow rowing crews to better judge their performances,” the city says.

The council also benefits. For the past decade, it has added recycled water to the lake from November to March “to counteract evaporation and ensure the lake is deep enough to support on-water activities in lower rainfall months.”

Until recently, council manually measured lake levels with a depth gauge and also referred to historical records when deciding how much water to add.

“Now, sensors deliver real-time information about conditions on the lake continuously,” Blood says.

We’re able to monitor air temperature, along with the water levels to forecast evaporation trends so that we know the best times to deliver the supply of additional water to the lake.

“The same data can help predict growth rates of the lake’s aquatic plants, allowing better planning for weed cutting, and a greater understanding of the lake’s ecology.”

The sensors and network infrastructure are funded through the Federal Government’s Smart Cities and Suburbs Program and the City of Ballarat, with Federation University contributing funding for the open data platform.

Broader use cases

It’s not just cities that are turning to IoT to assist with environmental management.

Mining companies have long used sensors to track air quality and dust levels around sites as part of environmental controls built into their licence to operate.

In addition, primary producers are also turning to environmental monitoring to increase yield, reduce over-watering and optimise other techniques such as the amount of fertiliser used.

“Agriculture is an industry well suited to IoT,” agrees Liam Landon, an associate market analyst at IDC.

For an industry that relies heavily on climate, sensing and interpreting hyper local environment information around weather and soil condition IoT will become increasingly important in the future, as climate change may drive increasing drought periods and more irregular rainfall.

“Sensor-based solutions that measure and analyse the use of inputs into agriculture such as water, fertiliser and feed will also become critical to Australian farmers operating in today's environment and seeking to increase yields while being more efficient.”